We are making great progress in our scoping review of frameworks describing health inequalities in observational public health research (protocol). We shared some of our early results with UCL Institute of Child Health Implementation Science Special Interest Group (SIG) last week, and an interesting question came up: what makes a theory or conceptual framework “new”?

It sounds like an obvious question. Most of the time, what we call “new” is really an adaptation — a shift, an extension, a remix of existing framework. We might add or remove an extra domain, a new component, a contextual layer specific to a certain analytical context. For instance, in public health we’ve seen countless expansions of existing frameworks to include social determinants of health (SDoH). These extensions are not necessarily understood as “new models,” but are variations — important and sometimes transformative, yet still anchored in the same conceptual roots. When does adaptation tip into originality? When does a reconfiguration become a new theory rather than a new setting for an old idea? And most importantly, why does it matter?

What tipped my thinking further was this LinkedIn post (Yes! – The new academic Twitter! ) by Dr Erica Thompson, as I quote:

Structural responsibility for model ownership, evaluation/validation and ongoing model maintenance and model risk management in large organisations/systems seems to me to be an increasingly urgent area to address…

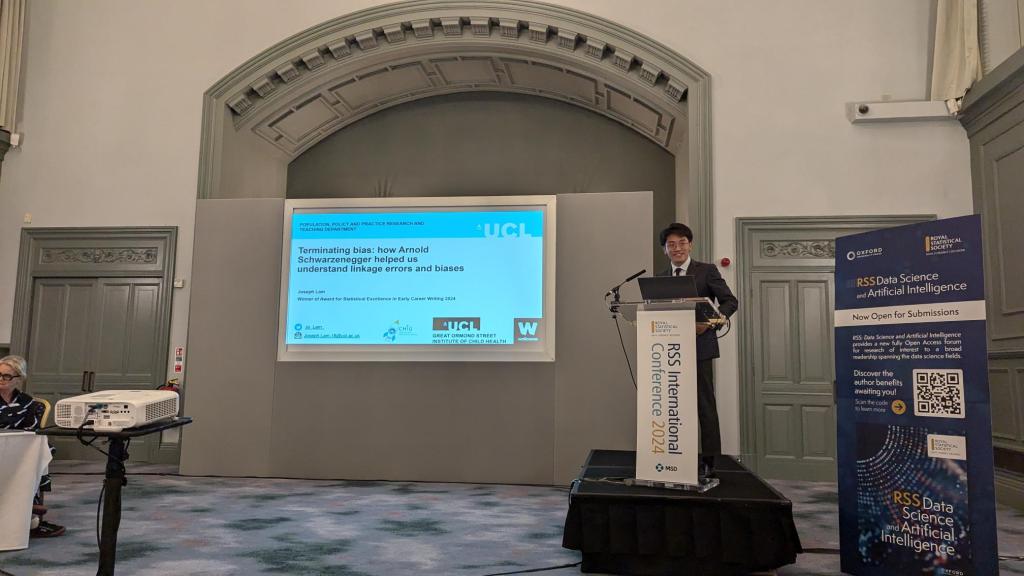

Originality becomes important important – as it implies some level of ownership, but mostly ongoing responsibility of model (theoretical) evaluation, maintenance and validation. On the flip side, as an academic community, one could argue that once a piece of information/knowledge/idea is shared, it is then the shared responsibility of all who engages in the space to maintain or refute. Probably not too similar to the replication crisis – where there is a spike of p=.05 effects – I could also expect an iceberg of theories/models/frameworks that fail to achieve their purpose. (but what are their purposes? This very nice paper highlighted 7 of them!)

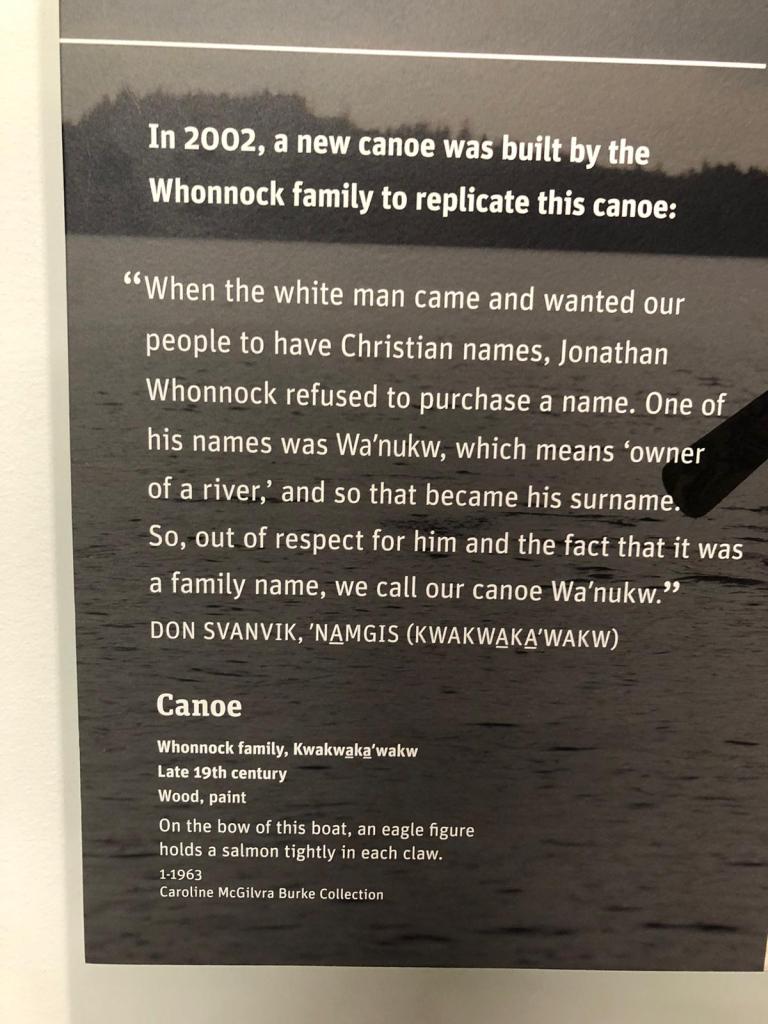

Back to the notion of what makes a model/framework “new” – Perhaps the answer lies not in the number of components added, but in the idea that underlies the model.

Take the SDoH framework from the WHO — a conceptual umbrella so broad that nearly any factor affecting health can be tucked underneath. It’s undeniably powerful, but also absorbent. Compare that to Andersen’s Behavioural Model of Health Services Use, which focuses on access: predisposing, enabling, and need factors shaping health service utilisation. Both speak to inequities, but they come from different conceptual spaces.

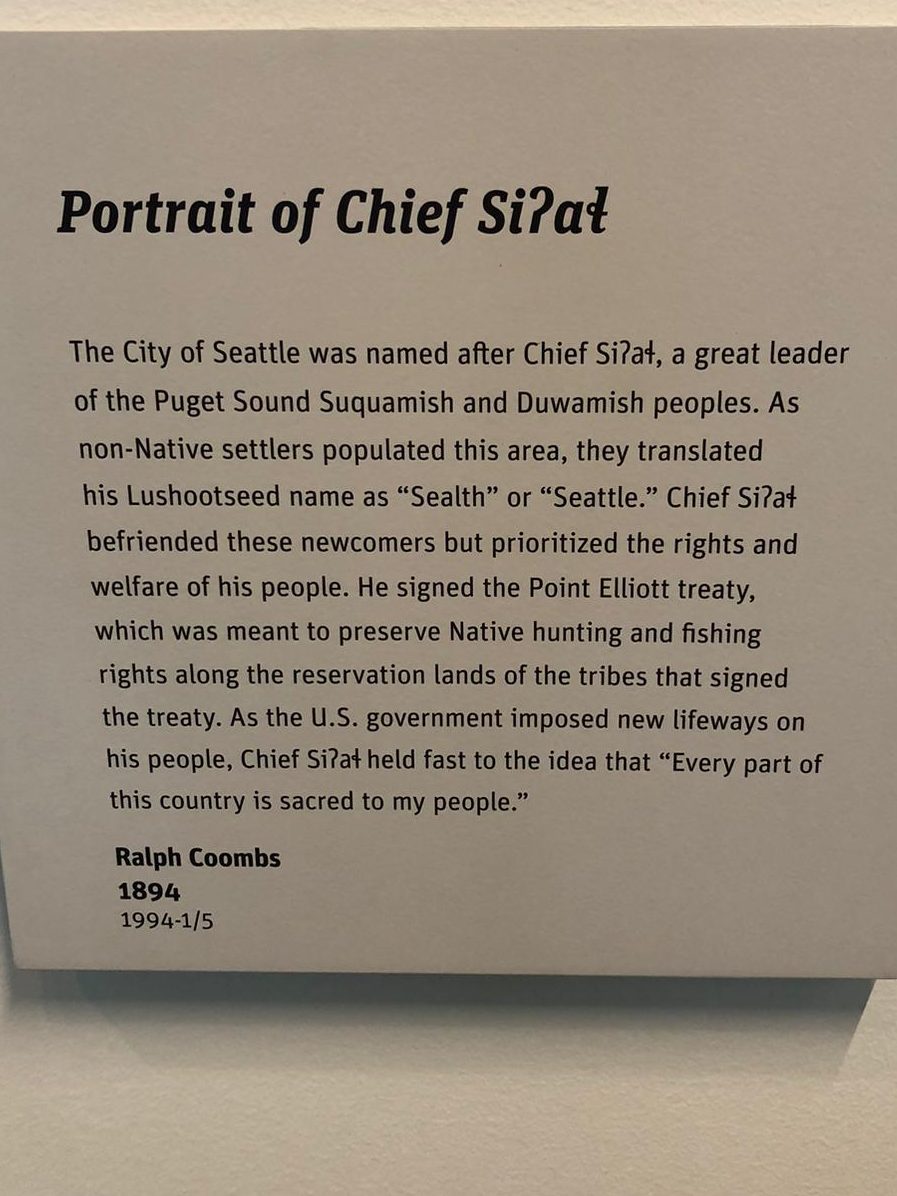

Then contrast those with Link and Phelan’s Fundamental Cause Theory — a framework born from a different philosophical stance altogether, one that resists being easily blended into SDoH. It argues that social conditions are not just one set of determinants among many; they are the persistent, structural roots that reproduce health inequalities even when mechanisms change.

In this light, the dominance of SDoH in public health science can have a kind of blender effect — pulling diverse frameworks into its orbit and smoothing over the conceptual distinctions that once made them powerful.

Meanwhile, we see a pendulum effect: theory and empirical research swinging apart. On one end, population health frameworks focus on structures and systems; on the other, individual-level behaviour models persist, often divorced from the macro contexts they operate within. Bringing these worlds together — harmonising the individual and the structural — is both intellectually challenging and practically necessary for meaningful intervention evaluation. However, there is this mismatch of spatial and temporal resolution of the effects that are operating at and across these levels. (hmm feels like a bigger idea is brewing…)

And yet, theory is not only a scaffold for model-building. As others in the discussion pointed out, theory should not be reduced to a checklist or a legitimacy badge. Too often, there’s a quiet academic anxiety: if we say we used the SDoH model, have we ticked the equity box? Implementation scientists know this trap well. Theories can clarify, but they can also constrain. We want them to guide, not to rubber-stamp. A truly new theory, perhaps, is one that opens up new lines of enquiry rather than closes them off.

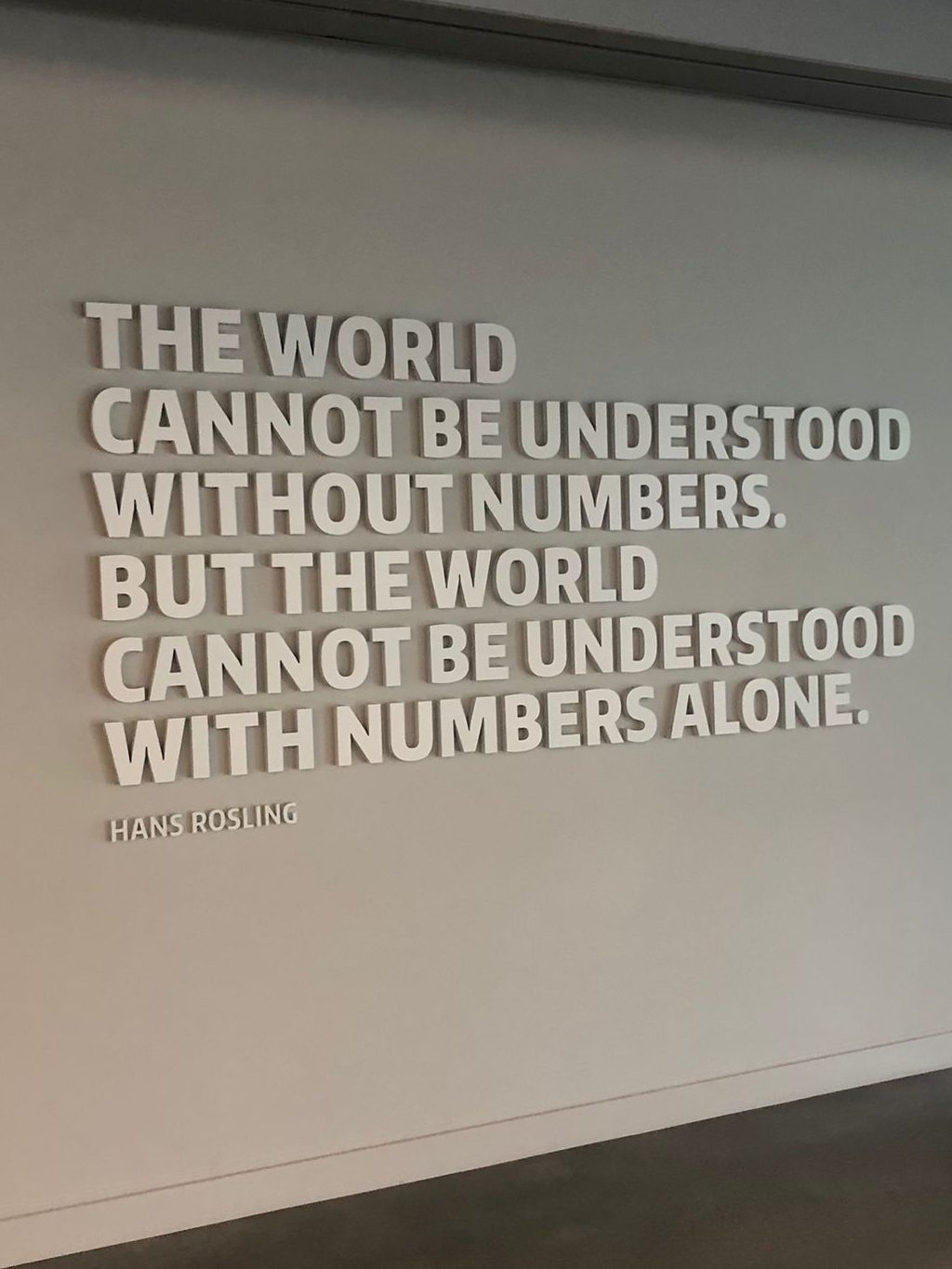

So maybe “newness” isn’t about novelty for its own sake. It’s about conceptual movement: when the underlying logic shifts, when the philosophical footing changes, when we begin to ask different kinds of questions — not just add more boxes to the framework.