I was honoured to have witnessed the unveiling of the inaugural ‘Children’s Plinth’ winning ceramic artwork ‘The Dog Who Went To Space’ at St Martin-in-the-fields last week. The artwork is part of the Mayor of London’s ‘Fourth Plinth Schools Award’ to put creative children centre stage as they paid homage to the Trafalgar Square’s historic Fourth Plinths.

Historically, women and children are often undercounted, deemed invisible, and their achievements not fully celebrated (see recent uproars on the Nobel Prize in Medicine). There are more statues of animals than statues of named women in London. Children are often discussed in a lens of potentials, what they can become, the next generation, and the future. But they are seldom appreciated as beings with intrinsic value, as valid and living contributors to knowledge generation, or valued members of society.

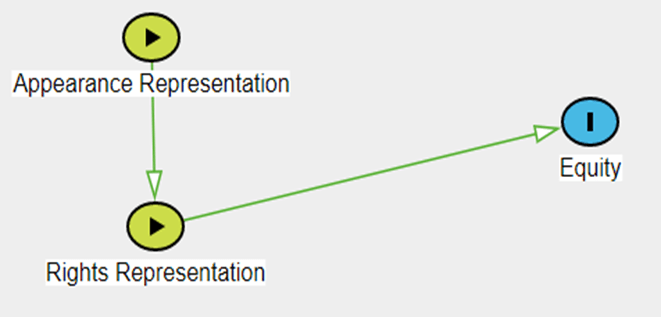

Who’s voice is heard? Who’s opinions are valued? Who is answering and making judgements to these questions? I observe a dominance of (a false sense of) a need for demonstrating entitlement. One has to earn their spot to be in the “room where it happens”. Under a façade of meritocracy, this need to show “added value” structures societal resource allocation and social policies. For example, the same line of reasoning underline the debates on minimum age for voting, eligibility for state pensions, mean-tested welfare system, and provision of health service. The same old Greeco-Roman attitude of citizenship persists: One has to contribute to society in a certain way for one to be recognised as a rightful citizen, a valued being. Initiatives on expanding participation, public and patient involvement, and Equality, Diversity and Inclusion all serve to challenge this old view, and expand: Young people’s merits is their being. You are valued for their being. (extend/substitute young people with any protected characteristics, gender, sexual orientation etc.)

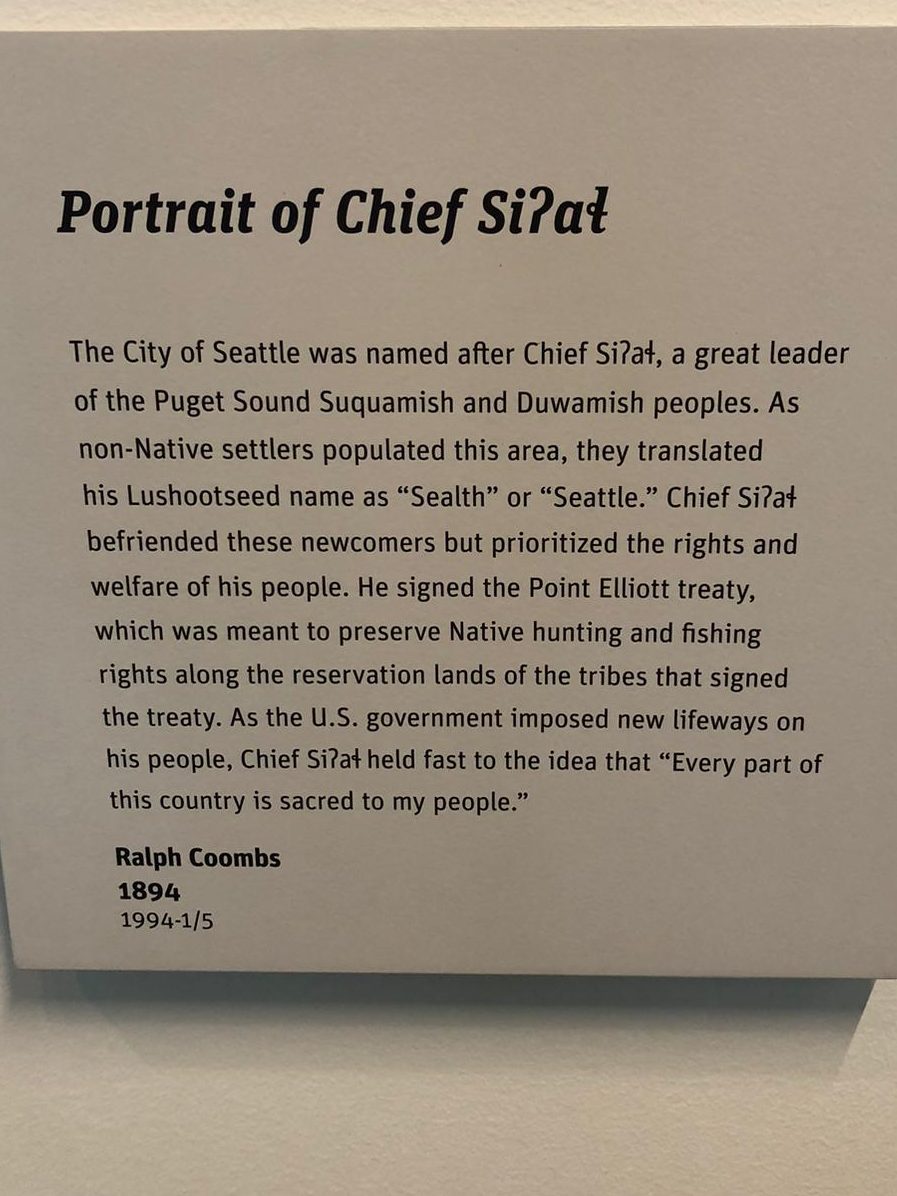

Photo by Hisham Zayadneh on Pexels.com

Academics and policymakers learn the keywords quickly – to give a voice to young people, and listen; but many young people still doesn’t feel that they have a voice, and their voices unheard. I want to highlight an amazing work led by Dr Lauren Herlitz and a group of young people who produced a podcast episode on their thoughts and experiencing interacting with primary care services. Lauren put the young people’s voices at the forefront, in a direct, raw form that does not filter out their anger and fear in their voices (listen to the podcast). These voices are now transformed into a different voice – as an academic paper, backed by the academic class. In my view, the academic class has the role and responsibility to amplify and project these voices: we are rooted in scientific methods, evidence and rigor, but has to transform and be (always) unsatisfied with the impact of our collective contributions.

The burden is now with us as adults, activists, researcher academic and policymakers. The public is engaged when relationships are built, when actions are seen, when voices are heard, when history and culture is respected. Investment in long-term planning of public engagement is crucial to inclusive and better research and policy-making practices.

I am deeply inspired by Mila Punwar and her ceramics artwork. Listen to Mila talk about her creations. Laika, the dog, was the first living creature to orbit the Earth. Laika died a few days into her mission, partly due to the process, but the crew never prepared for more than 7 days of food. Laika was bound to be sacrificed. Young people’s voices are here to be projected upwards, to the outerspace if need be. Their voices cannot die like Laika.

Who do we value?